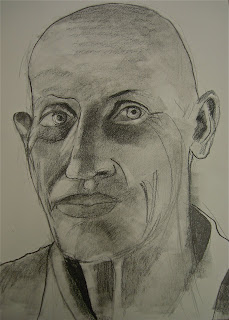

(The top image is my portrait of Troy. The others are examples of Troy's work. They are arranged more or less in chronological order with the newest at the top and the oldest at the bottom.)

(The top image is my portrait of Troy. The others are examples of Troy's work. They are arranged more or less in chronological order with the newest at the top and the oldest at the bottom.)Troy lives with his wife, the artist Claudia Flynn, in a 300-year-old farmhouse in southern Rhode Island. Over the years he hasn’t so much remodeled the house as deconstructed it. Within its post and beam bones there is a stimulating unpredictability and a sense of controlled chaos. It seems that every wall that doesn’t bear weight has been removed. Windows have been expanded to let in as much light as possible. At one end of the first floor there is an opening into the old stone cellar. As you descend on a sculptural steel stairway each step rings quietly like a lightly struck gong. Below, the utilitarian stonewalls that hold up the house have been modified into a fluid grotto, designed by Troy and Claudia, with an inviting wrap around stone bench. This space, which is used as an art gallery showcasing sculpture, paintings and ceramics, is totally unexpected and yet it feels just right.

Upstairs, on the third floor, that was once a cramped attic, Troy has punched through the roof and installed a glass ceiling for their bedroom and his indoor studio. The area where they sleep and he draws is accessed along a narrow ledge that is open to the stairs.

The couple’s bed is two steps from his drawing table.

“I’ve always hated commuting,” he told me.

This space that you find on the third floor, at the top of a flight of well worn, too-narrow stairs, is highly unexpected, as is the gallery in the basement, but these areas are charming and engaging rather than disorienting. This is quirky architecture, but the unconventional style is not aggressive or confrontational. In Troy’s house art is everywhere and it seems that few rules apply except the one that says make people feel welcome.

Next month on February 16th, Troy will turn seventy-six. He is strong, lean and fit.

“Every ten years,” Troy says. “I run the New York City Marathon. Slowly, but assuredly. It is a wonderful way to see the city. Thank goodness, I don’t have to do it again until 2014.”

Routinely, he gets up at dawn and rides his bike to the beach.

“What is it to the beach,” I asked. “About a mile?”

“1.4 miles,” he said.

Following the bike ride, he runs on the beach. Usually, at that hour of the morning he has it all to himself.

Troy seldom comes home from the beach empty handed. He brings back smooth white stones, driftwood that is twisted in interesting ways, rusted steel posts, fishing lures, shells, seaweed, anything, everything. All of this is raw material for sculpture. It will be combined, recombined and combined once more until it takes artistic shape. Sometimes it will be welded to larger found metal, sometimes paint is added, sometimes words spiral over curved surfaces, sometimes recognizable objects appear. These sculptures of recycled materials are placed outdoors in related groups. Over time vines twist over them and reeds grow up around them. Some crevasses become moss covered and others sprout seedlings. This process of Troy’s has been going on around the farmhouse for more than thirty years. As a result his yard resembles the briar patch of a very hip Brer Rabbit.

One area of the yard is best visited when lite by the full moon. There are several sculptures, ranging in size from wheel barrels to Volkswagens, made of rusted metal that is twisted and welded to hold smooth white stones. Some of the stones resemble eggs and are held aloft in circles at the ends of spindly metal rods. Other stones, the size of bowling balls, are packed tightly into welded metal frames that suggest they have been mined and are being brought to the surface in ore carts. In the moon light the rocks glow and the sculptures cast patterned shadows that slowly move across the ground.

The 17th century farmhouse, the beach, the personal sculpture park: these days Troy’s life is spread out in a way that is only possible if you live rurally. In contrast to this, as a young man he lived in some of the densest urban areas in the country: Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Newark.

He went to Carnegie Melon University to study architecture, and married a fellow student. They had two sons, Troy Eric, an actor and Anker Carl, an architectural designer and artist. Upon graduating, he won the statewide John Stewardson Memorial Traveling Scholarship Competition to continue his studies abroad. These days the award is $10,000. In 1958 it was worth $1,500, still enough to get him to Europe for an extended visit.

Troy’s career as a professional architect was high powered. He won numerous prizes and awards from organizations promoting progressiveness in the field and placed among the finalists in competitions for prestigious projects. He worked with people who are unknown to the general public – Oskar Stonorov, Tasso Katselas and Louis Kahn - but make aficionados weak in the knees. He also returned to Carnegie Melon to teach architecture.

At Carnegie Melon, he joined a rag tag group of professors, students, and community activists who tried to save Forbes Field from the wrecking ball by creating alternative uses for the ballpark. Home to the Pittsburgh Pirates, it was recognized as the most beautiful in the Major Leagues. “It was one of those stadiums that cupped its hands around players and spectators, and I was passionate about saving it.” He advocated, “Do not tear this structure down, instead turn it over to the community.”

Trying to save Forbes Field would not be his last quixotic fight against development.

During his years in Pittsburgh, troy spent a lot of time in the Hill District, going to jazz clubs like the Hurricane and the Crawford Grill No. 2. He took along his drawing pad to sketch the scene. This imparted a special status that made up for the fact that he was often the only white guy around.

Troy observed that “development” often meant bulldozing some area of the poor, black community and appropriating it for the benefit of the folks downtown. He initiated the first university-based community design center, Architecture 2001. It was housed in an old drug store at 2001 Centre Avenue in the same neighborhood as the jazz clubs he frequented. The organizers, many of who were ex cons and heroin addicts met with architecture students to imagine projects that would actually benefit the people living in the Hill District. The team received grants and national acclaim for their built and un-built project designs.

In 1974, he was invited by the New Jersey Institute of Technology to be a founding member of the architecture school. He was selected because of his reputation as an activist who viewed design and development as a political process in which one could advocate for members of the community who wouldn’t otherwise have a voice. In three decades of living teaching and practicing architecture in Newark, his studios always involved the city. One of his favorite activities was to take his students to the grittier parts on town, sit on a curb and draw the dilapidated old brick buildings.

He created designs to save threatened industrial areas. His students redesigned and rebuilt a fire damaged, wood frame, 19th century house. Out of the wreckage came twelve units of off campus housing with a solar greenhouse and community spaces, the first of its kind in the country.

Troy’s base of operations in Newark was and is an 18th century toy factory. When he first arrived there, a young professional living and working in a run down industrial space was just weird. Now, of course, it is de rigueur. Troy currently maintains an office, which he shares with his son Anker, in that same toy factory, The Dietze Building, now a thriving artists colony.

By 1977, Troy had begun to yearn for a different kind of life. He undertook a four-year search of the east coast for a place near the ocean. Finally, he found the south shore of Rhode Island. He has been happily living and working in the farmhouse, 1.4 miles from the beach, ever since.

Troy and Claudia are currently preparing for DUET, a show of their work at the Galerie Vidourle Prix in Sauve, France. The gallery co-director is Aline Crumb, the wife and collaborator of R. Crumb, counterculture icon of the highest order. The two are delighted with the opportunity for a solo exhibition in this venue.

One of the paintings Troy has completed for the show in France is a self-portrait. He appears as a rather scrawny, naked figure pushing one of his sculptures. I saw the actual sculpture out in the yard. It had wheels, but they were sunk in the frozen ground and it must weigh a couple of hundred pounds. It wasn’t going anywhere. The picture stuck in my mind. It reverberated for me as an image of the artist as Sisyphus. Sisyphus is punished by the gods for, among many things, tricking death. His particular punishment is to roll a huge rock up a mountain for eternity. Before he can reach the top the rock always rolls down and he must start all over again. An artist is always pushing his work up hill, striving to make it to the top, but he never does. It is never perfect. There is always the next drawing, the next painting. He always has to start again. Of course, it is not a perfect analogy. For most artists the process is not a punishment, but a discipline, often a joyful one.

I asked Troy if this relationship of his self-portrait to Sisyphus had occurred to him. He said, “As a matter of fact I did think of that. Every time you pick up a piece of charcoal it is a challenge and a struggle. It is not easy and you never reach the top, but that is a good thing. What would you do if you reached the top? Retire?”

In this life, there is no danger of Troy West ever retiring.